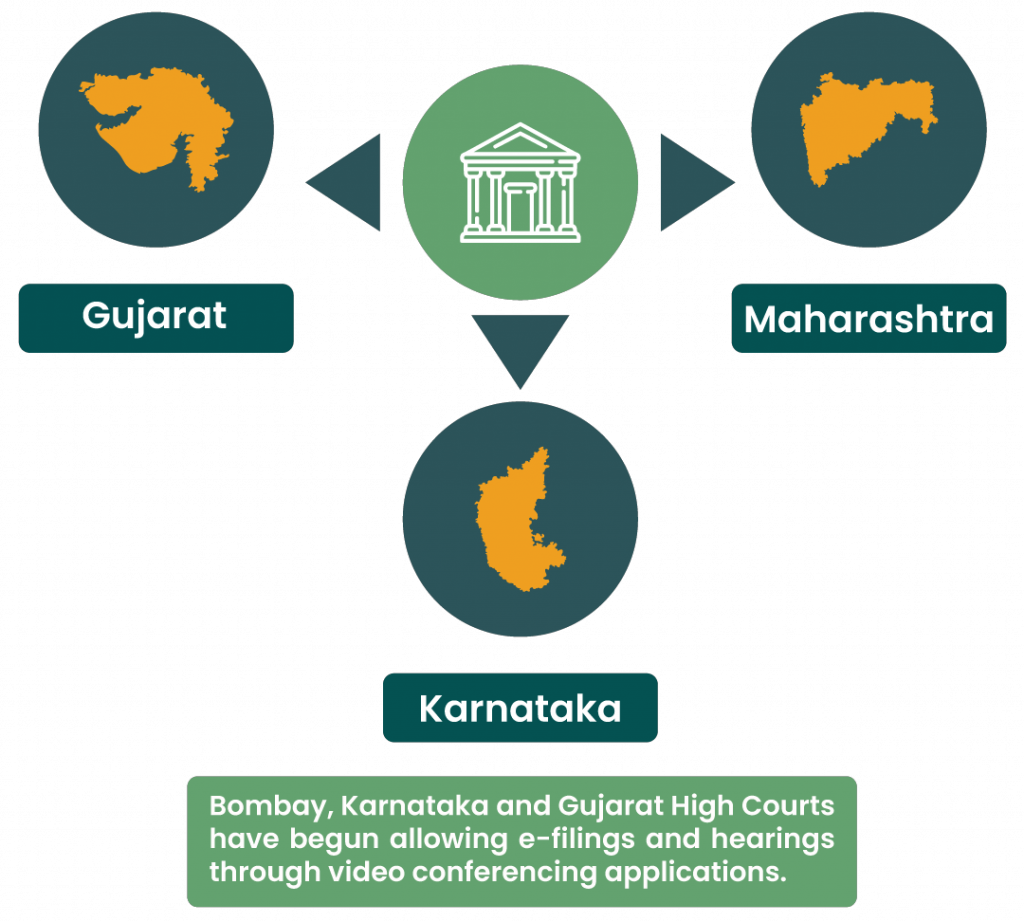

The Pandemic saw the Supreme Court of India take unprecedented measures by barring physical entry into the court premises. Urgent hearings were held via video conferencing, and lawyers’ chambers were sealed. Multiple High Courts, including the Bombay High Court, Karnataka High Court, and Gujarat High Court, have also followed suit. E-filings and hearings through video conferencing applications like Vidyo, Skype, WhatsApp, etc. have become commonplace.

The ambitious e-Courts mission has seen initiatives like e-filing, virtual courts, video conferencing, and online case status. As a result of this initiative, digitisation appears to be knocking at the doors of justice. Government reports even suggest that planning has begun on using AI/ML and blockchain technology for automating judicial processes. Work is already ongoing for transferring judicial data to the cloud. Thus, the ‘Corona era’ has created a need for “contact-free” Online Dispute Resolution (“ODR”).

Statistics show that non-service or “ineffective” service is a major reason for delays in the judicial process. Let’s, therefore, analyse a crucial aspect – the legal validity of service through emails and messaging applications like WhatsApp. Here’s a look at what courts have held:

- The Supreme Court of India in Central Electricity Regulatory Commission v. National Hydroelectric Power Corporation Ltd had issued directions for effecting service through emails.

- Many of us know Justice G. S. Patel’s observations in Kross Television India Pvt Ltd & Anr Vs. Vikhyat Chitra Production & Ors. The Justice held that the purpose of service is to put the other party to notice. Where an alternative mode (email and WhatsApp) is used and service is shown to be effected and acknowledged, it cannot be suggested that there was ‘no notice’.

- The Delhi High Court in Tata Sons Ltd & Ors. Vs. John Doe(s) & Ors., allowed the Plaintiff to serve the summons on one of the Defendants through WhatsApp, text message, and email, and to file an affidavit of service.

- Rohini Civil Court in Delhi accepted the blue double-tick sign in a WhatsApp message as valid proof that the message’s recipients had seen a case-related notice. The Karkardooma Metropolitan Court in Delhi allowed a woman to serve a summons to her husband in Australia through WhatsApp.

- Justice G. S. Patel in SBI Cards & Payments Services Pvt. Ltd. v. Rohidas Jadhav reiterated the stance by accepting the service of notice through WhatsApp after finding that the notice served was not only delivered but the attachment was opened as well.

- The Bombay High Court in Dr Madhav Vishwanath Dawalbhakta & Ors. v. M/s. Bendale Brothers took note of the concept of substituted service in Order 5 Rule 20 of the Code of Civil Procedure. The Court observed that it can take into account the modern ways of service available due to internet connection. It can be served also by courier, email or WhatsApp, and the soul of the service is to know the proceedings delivered to the defendant or the contesting party.

- The Supreme Court in Indian Bank Association & Ors vs Union Of India & Anr and the Bombay High Court in Ksl and Industries Ltd., Vs Mannalal Khandelwal and the State of Maharashtra permitted service through emails.

The legal underpinnings

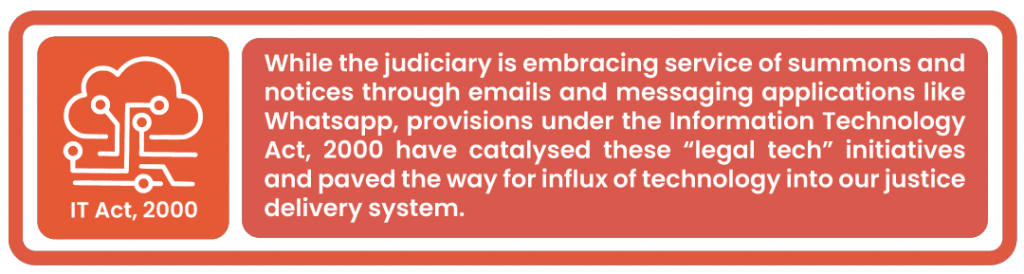

The judiciary is embracing the service of summons and notices through emails and messaging applications like WhatsApp. Additionally, provisions under the Information Technology Act, 2000 have catalysed these “legal tech” initiatives. This has further paved the way for an influx of technology into justice delivery.

Let’s proceed to understand the underlying provisions of law that provide legal backing to this concept:

- Section 4 of the Information Technology Act, 2000 (ITA 2000) gives legal recognition to electronic records;

- Section 3 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (IEA 1872) defines “evidence” to include all documents including electronic records;

- Section 5 of the ITA 2000 gives legal recognition to electronic signatures;

- Section 10A of the ITA 2000 validates contracts formed through electronic means;

- Sections 11, 12, and 13 of the ITA 2000 govern attribution, acknowledgement, and despatch of electronic records;

- Section 65B of the IEA 1872 provides for the admissibility of electronic records;

- Sections 85A, 85B, and 85C of the IEA 1872 support the evidentiary value of electronic records and electronic signatures.

Thus, the above provisions favour the issue, communication, and recognition of electronic records for various purposes, including legal notices. Interestingly, the Delhi High Court has also made rules regarding the service of legal notices through email. The Bombay High Court has also formulated the ‘Bombay High Court Service of Processes by Electronic Mail Services (Civil Proceedings) Rules, 2017‘, bringing some relief to litigants in commercial disputes.

To email, or not to email – service of private notices and the law

Relevant laws allow the IT department and the GST Department to issue notices to assessees via email. But an interesting question arises — are private notices from one party to the other valid if communicated via email?

Firstly, serving private notices via email in cases where the law does not necessitate one will have evidentiary value so long as it fulfils the requirements of the ITA 2000.

Let’s look at some cases where the law statutorily requires the aggrieved party to serve a legal notice on the counter-party:

- Notice for Breach of Contract: Legal notices by email shall be valid so long as the corresponding contracts expressly permit the giving of notices by email. They shall have evidentiary value so long as they fulfil the requirements of the ITA 2000.

- Demand Notice under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016: Rule 5(2) of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy (Application to Adjudicating Authority) Rules, 2016 permits delivery of the demand notice by email.

- Notice under Section 138 of the Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881 for the dishonour of cheques: Section 138 does not prescribe any particular mode of service of the demand notice but merely requires a “notice in writing”. Accordingly, giving a demand notice to the drawer of the cheque via email will be an effective service. Again, it will have evidentiary value so long as it fulfils the requirements of the ITA 2000.

- Arbitration: The request for arbitration, the appointment of the tribunal, the statement of claim, interim reliefs, and the responses — all can be served electronically. Supporting this contention is the Delhi High Court judgment in the case of Bright Simons v. Sproxil, Inc. In addition, Sections 24 and 29B(3)(a) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 enable arbitral tribunals to decide the dispute solely based on pleadings, documents, and submissions without recourse to oral hearings. Additionally, Section 7(4)(b) of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 treats electronic communication of an arbitration agreement as an arbitration agreement in writing.

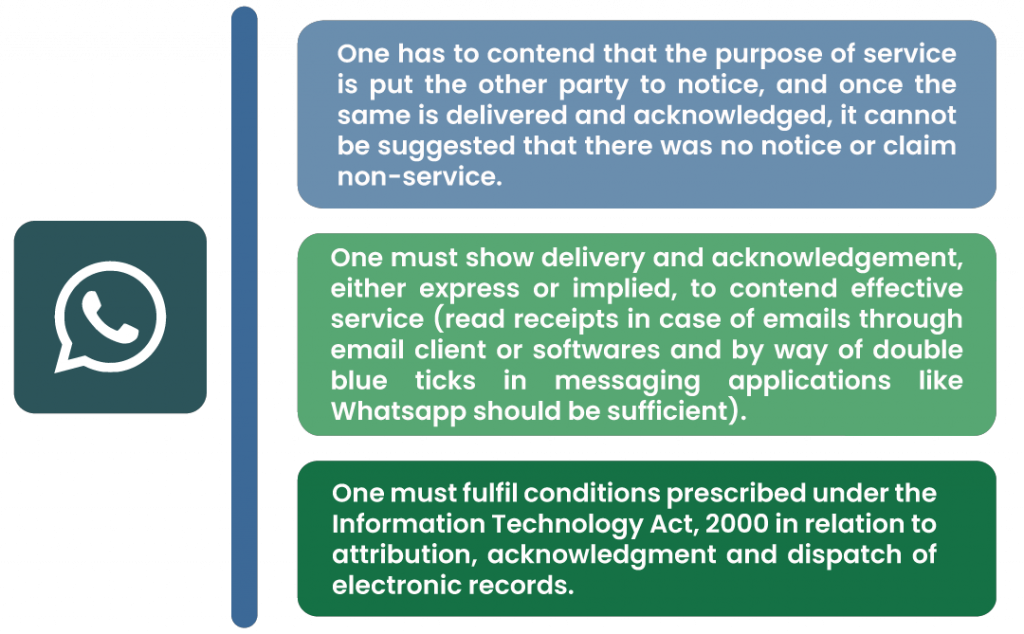

In summary, to be able to demonstrate that service through email and messaging applications like WhatsApp is effective:

Adapted from Online Dispute Resolution: Validity Of ‘Service’ Through Emails, Whatsapp And Messaging Applications, originally published on LiveLaw.