By Ananya Singhal and Dhriti Hundia

India houses the largest democracy in the world. The Constitution of India – the country’s supreme legal document – safeguards the rights and outlines the responsibilities of Indians. In addition to this, the three pillars of our system – Executive, Legislative and Judiciary – are collectively working to provide great governance, greater laws, and the greatest level of enforcement.

Any citizen can approach the judiciary in case of infringement of his right. However, the Indian judicial system has been plagued with the below-mentioned challenges, which are hampering its function of dispensing timely, cost-effective, and efficient justice:

- Lack of use of technology

- Exorbitant “cost of litigation”

- Insufficient budgetary allocation

- Complex procedures and inefficiencies

- A massive backlog of cases and vacancies

International trade, foreign investment, and industrial policy and promotion are the backbone of an economic superpower, but India’s progress is being weighed down due to these challenges, and as far as the common man is concerned, accessing justice has become a costly affair.

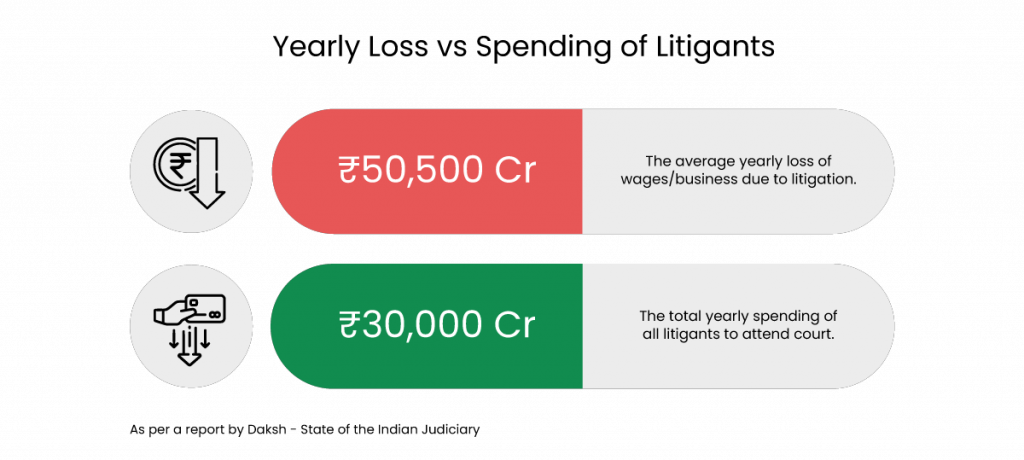

As per a report by Daksh (State of the Indian Judiciary), the average yearly loss of wages/business due to litigation is approximately INR 50,500 crores, and the total yearly spending of all litigants to attend courts is approximately INR 30,000 crores. In such an environment, Alternative Dispute Resolution (“ADR”) mechanisms have stood their ground.

ADR mechanisms have helped the judiciary to dispose of a plethora of cases, but the impact of ADR can be multiplied if it is coupled with technology. Therefore, it is important to catalyse the concept of Online Dispute Resolution (“ODR”) in the country, unlock its true potential, and enable the resolution of disputes in a collaborative online environment, thereby making it quick, cost-effective, and accessible to all—common people, companies, institutions and even Governments.

Can India clear the backlog?

It is crystal clear that the current machinery will most likely never be able to solve the backlog of cases pending. That is where innovation, technology, and enthusiasm come to the rescue.

When doctors couldn’t reach everywhere, entrepreneurs invented telemedicine and remote clinics. When retailers couldn’t cross geographies, entrepreneurs developed online marketplaces. When restaurants were limited in terms of seating capacities, entrepreneurs provided last-mile deliveries. When gyms couldn’t train large audiences, entrepreneurs provided digital platforms. When banks couldn’t open branches everywhere, entrepreneurs provided online banking infrastructures. And when courts are overburdened, entrepreneurs are now getting creative.

Legaltech, or regtech, is all set to launch anti-viruses in various shapes, sizes, and forms. In India, technology is empowering the dispute resolution mechanism through digitization. Startups like Presolv360 are leveraging technology and artificial intelligence to facilitate the online resolution of disputes for businesses and individuals, using ADR mechanisms like arbitration, mediation and negotiation. Instead of knocking on the doors of courts and getting sucked into tedious litigations, more and more companies are opting for Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) alternatives which are quick and affordable. NBFCs that Presolv360 has been working with have got resolutions within weeks, instead of waiting for years while pursuing litigations or in-person arbitrations.

Speedy justice is especially important for today’s demographic. When funds are transferred anywhere in the world within seconds, loans are disbursed within minutes, a 10-minute wait time for Ubers is tagged as bad luck, and 30-minute pizza deliveries also seem to be taking too long, can anybody be asked to wait for 13[1] years for justice (that is the average time it takes for case disposal in Indian courts)? Presolv360 has, in fact, settled cases within just a few hours of negotiations between disputants.

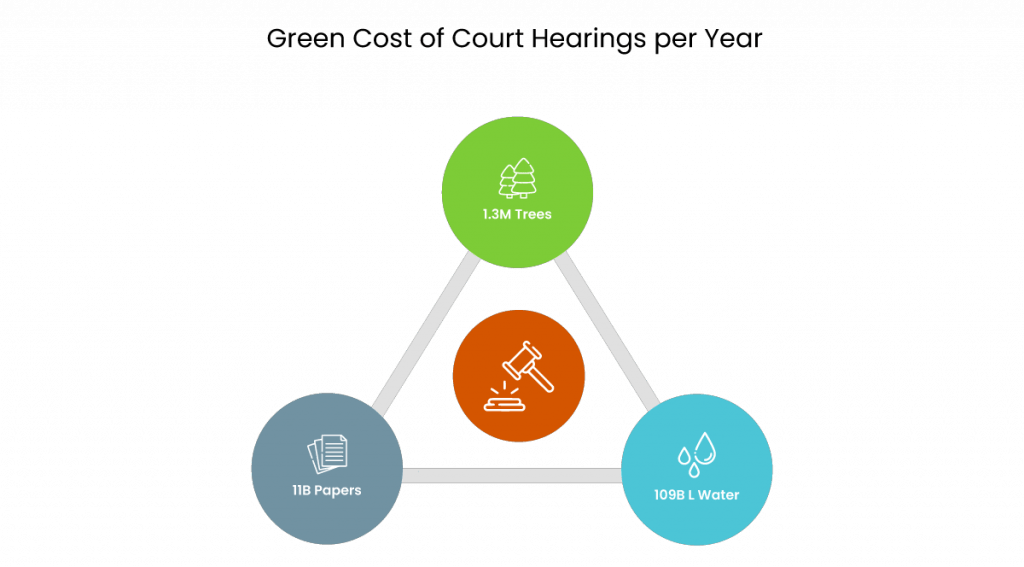

As the world moves digital, can people and businesses be expected to print heaps of documents and carry them to courts for years (it is worthwhile to note that 11 billion sheets[2] of paper are used each year in Indian courts, and the green cost of court hearings translates to 1.3 million trees and 109 billion litres of water being consumed[3] every year)? Presolv360 has digitized the entire process and is also integrating blockchain technologies in its mechanisms to ensure tamperproof functioning in a paperless environment.

Presolv360’s experience with handling several disputes across categories and sizes is that ODR (considering the nascency of this sector) is especially effective for small-value disputes that can be resolved efficiently and quickly without the need to meet in person. Such vanilla disputes, in fact, comprise a large chunk of cases being filed in courts, and if resolved outside courts, it will significantly free up the courts’ backlog and burden too, allowing them to focus on cases more serious in nature — on matters of law and jurisprudence and on national security.

So what exactly is ODR?

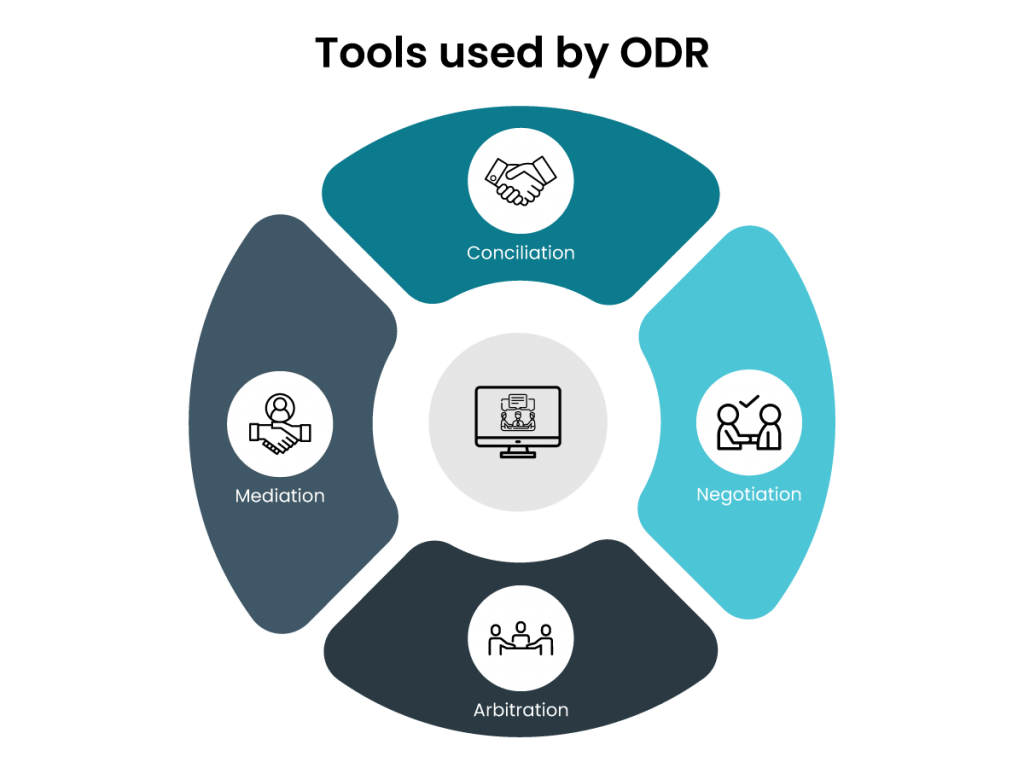

Online Dispute Resolution (ODR) is a mechanism to resolve disputes between parties harmoniously outside of court with the help of technology. It includes the use of various mediation, negotiation, conciliation, and dispute resolution tools including arbitration.

It lets any individual or organisation resolve their disputes from anywhere at a fraction of the time and cost as compared to the traditional recourse of litigation. ODR has developed alongside e-commerce since it seemed natural that a dispute originating in cyberspace be resolved completely online. Today, the use cases for ODR have broadened, and its application is present across industries. The integration of ICT tools into dispute resolution holds immense promise to overcome the challenges that have plagued the traditional court and ADR systems.

Online Dispute Resolution in India – Benefits and Challenges

The use of ODR in India is at a nascent stage and is starting to gain prominence day by day. A joint reading and interpretation of various provisions and rules of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (“ACA 1996”), Information Technology Act, 2000 (“ITA 2000”), and Indian Evidence Act, 1872 (“IEA 1872”) provides for resolution of disputes via ADR and the applicability of the same in an online environment. However, none of the laws/statutes provides a clear recognition of ODR.

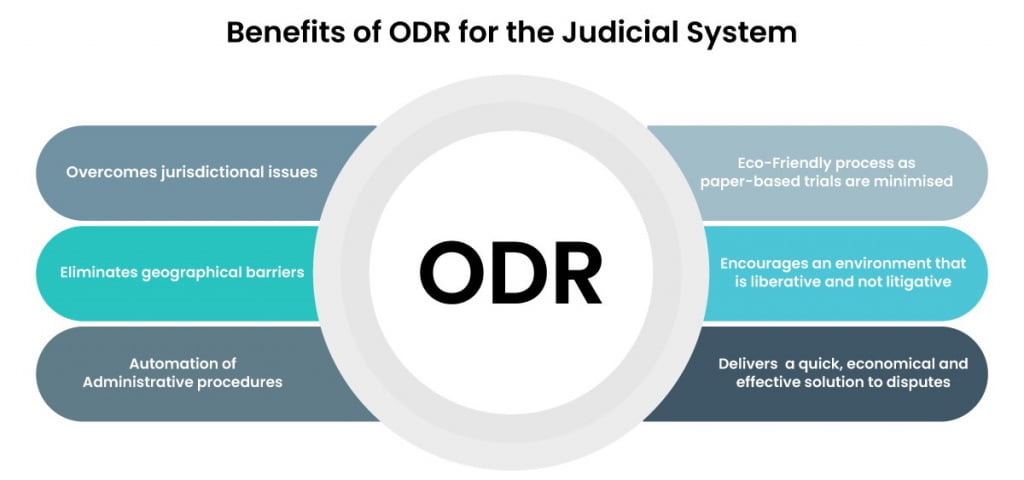

To surmount the aforementioned challenges faced by the Indian judicial system and scale-up ADR in India, an infusion of technology in dispute resolution is inevitable. The usage of ODR as a means for resolving disputes has a number of benefits, especially in the context of the Indian scenario. Here are a few mentions:

- Overcomes jurisdictional issues

- Eliminates geographical barriers

- Automation of administrative procedures

- Improves the efficiency and productivity of dispute resolution professionals

- An eco-friendly process as the paper-based trail is minimised

- Encourages an environment that is liberative and not litigative

- Delivers a quick, economical, and effective solution to disputes

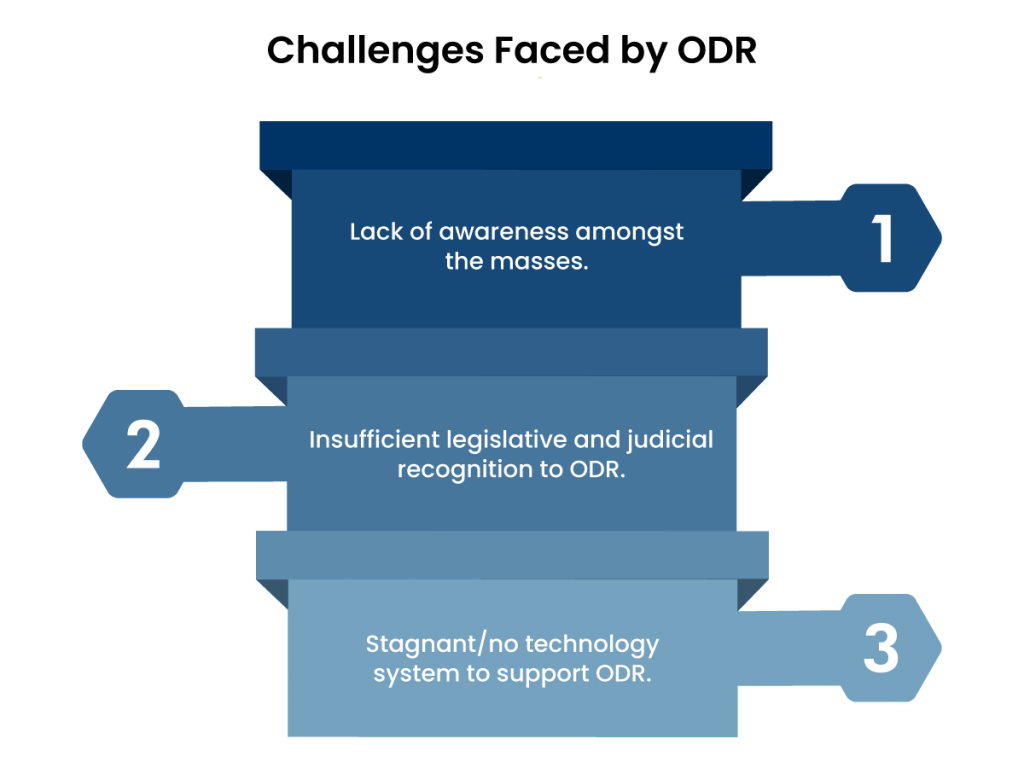

The implementation of ODR in India, however, is facing the following challenges due to which it has not been able to reach its full potential:

- Lack of awareness amongst the masses

- Stagnant/no technology system to support ODR

- Insufficient legislative and judicial recognition of ODR

Which industries can ODR be used in?

Online Dispute Resolution is especially useful for resolving medium to small ticket disputes. For example, the insurance and e-commerce sectors are highly organised and technologically adept. These are sectors where ODR can be integrated seamlessly. Rental leases are high-volume, low-value disputes, making ODR an attractive option for the industry. Government disputes with citizens for various services offered by the government are often the causes of civil litigation. Implementing ODR for such disputes could be very beneficial and also help reduce the burden on the courts. Utilities and telecom disputes are another industry which can benefit from the use of ODR.

Hence the sectors relevant to ODR can be:

- Insurance

- E-Commerce

- Housing

- Telecom

- Government Utility Services

Why should you opt for ODR?

On average, it takes about 1,445 days for a litigant to get a dispute resolved in India. Besides the visible legal costs that accrue, it is also essential to factor in the opportunity cost that might include lost wages or unproductiveness of assets (like machinery and capital), and the toll court litigation takes on the individual mentally. ODR offers the promise of a faster, more accessible, and more convenient option for many individuals and companies to resolve disputes online[4].

Originally, arbitration was intended as the alternate option available to court litigation for various kinds of disputes. But with the passage of time today, this method itself has become cumbersome and expensive.

As of July 27, 2020, there are around 33.47 million cases pending before the District Judiciary and 4.46 million cases pending before the High Courts, according to the e-Courts website[5].

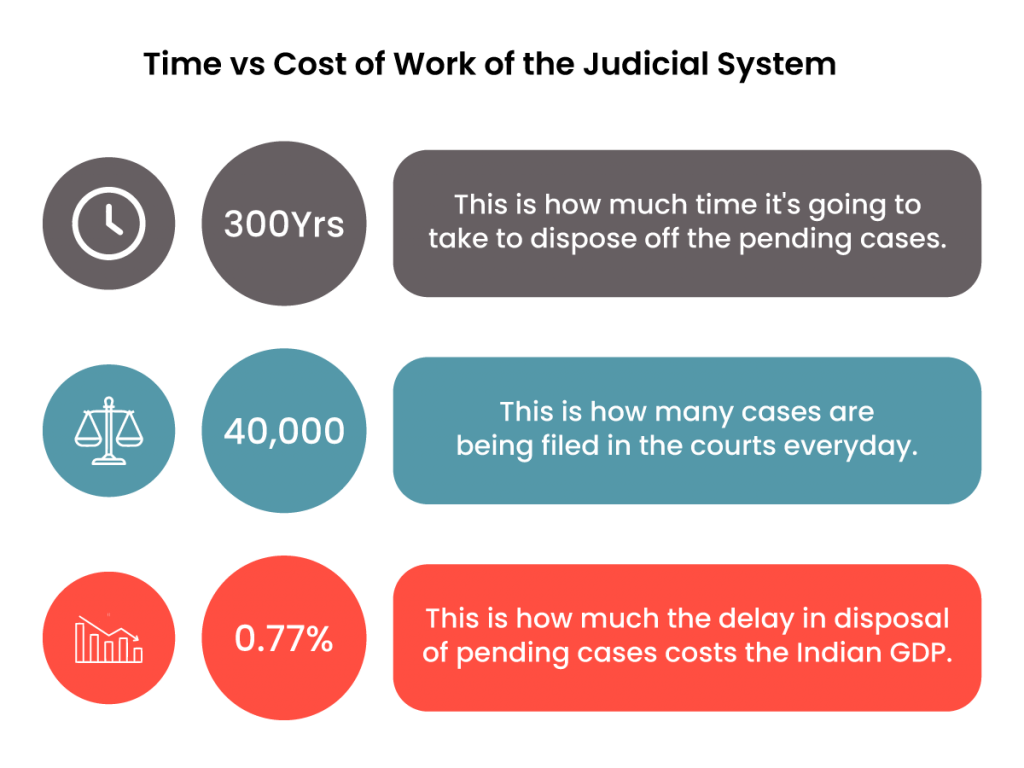

As per studies, this pendency of over 3 crore cases is going to cross the 15 crore mark by 2050[6]. This pendency of cases in Indian courts itself is pegged to take over 300 years[7] to be resolved. Approximately 40,000[8] cases are still being filed every day in courts, and the pandemic exacerbated the situation even further. It doesn’t make it easier that India is the most litigious country in the world. The economic cost of this delay is as much as 0.77%[9] of the Indian GDP!

One may ask: are there real consequences to the country because of these pendencies of cases (in addition to the obvious economic cost)? Here are a few things to consider:

- The common man’s faith in the justice system is at an all-time low.

- Delayed dispute redressal mocks the constitutional right to property and the human right to dignity.

- Foreign investors are increasingly doubtful about the timely delivery of justice, which affects the success of programs like ‘Make in India’. Several investors and organizations have, in fact, written India off from their plans only because of an inefficient dispute redressal mechanism, which is time-consuming, resource-heavy, and uncertain.

- The large number of pending criminal cases is exceptionally worrisome. Firstly, it denies access to justice to a large number of victims of crime. And, secondly, because of the slow progress of criminal cases, a large number of undertrial prisoners continue to languish in jails. Sometimes, they end up spending more time in jail as undertrials than the prescribed term of imprisonment for the crime they have been accused of committing (this is the situation for two-thirds[10] of the jail population in India).

- Economic reforms remain only on paper without a speedier justice system, which is a foundational pillar of any society or nation.

- The credibility of constitutional governance itself is getting steadily eroded.

Use cases of Online Dispute Resolution in India

Various organisations in different domains within the country have begun implementing the concept of ODR or using technology for the speedy redressal of grievances/disputes. Here are some examples:

- Online Consumer Mediation Centre (“OCMC”): Started as a pilot project by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Government of India, this platform specifically deals with the resolution of e-commerce consumer disputes. OCMC aims to provide state-of-the-art infrastructure for resolving consumer disputes through in-person and online mediation. The aggrieved consumer must register on the platform and provide details of the dispute along with the resolution sought from the e-commerce company. The parties can conduct online negotiations or opt for mediation, in which case OCMC appoints a mediator and conducts the proceedings online.

- RTI Online: The Department of Personnel & Training, Government of India, has built a portal for filing Right to Information applications and first appeals online with respect to ministries, departments, and other public authorities of the central government. It also features a payment gateway for the payment of fees. The updates regarding the application/first appeal are communicated via email and SMS and the orders are uploaded on the portal itself. The Central Information Commission provides for the filing of second appeals online through its portal. It issues notices of hearings and facilitates the uploading of pleadings through its portal. The hearings and proceedings are conducted via video conferencing using the network of the National Informatics Centre (“NIC”).

- MahaRERA Conciliation and Dispute Resolution Forum: With a view to facilitating amicable conciliation of disputes between promoters and allottees, the Maharashtra Real Estate Regulatory Authority (“MahaRERA”) set up the MahaRERA Conciliation and Dispute Resolution Forum. An aggrieved allottee can lodge a formal complaint online against the builder via the MahaRERA Complaints Portal, add details, state the reasons for conciliation, submit relevant documents, and make the payment to submit the complaint.

- Open Network for Digital Commerce (“ONDC”): ONDC is a government-backed e-commerce interoperability programme, the pilot of which has been launched in a few cities. A new-age system, ONDC is developing a dispute redressal framework which will act as a premise for an ODR platform, that will be used to resolve disputes between the relevant stakeholders within the Network.

- Unified Payment Interface (“UPI”): The National Payments Corporation of India (“NPCI”) issued a circular on April 11, 2022, stating that all the UPI participants must implement ODR systems to resolve disputes and grievances of failed transactions. This instruction applied to all participants such as banks and mobile applications. Interestingly, the Reserve Bank of India (“RBI”) also issued a circular in August 2020 and mandated all authorised Payment System Operators (“PSOs”) to implement ODR systems by January 2021.

- Many regulators and government bodies have also started embracing ODR for quick and easy redressal of disputes. SEBI has the SEBI Complaints Redress System (SCORES), IRDA has the Integrated Grievance Management System (IGMS), RBI has its Complaint Management System (CMS), and the Department of Administrative Reforms & Public Grievances has the Centralized Public Grievance Redress and Monitoring System (CPGRAMS), to quote a few examples.

Online Dispute Resolution(ODR) around the world

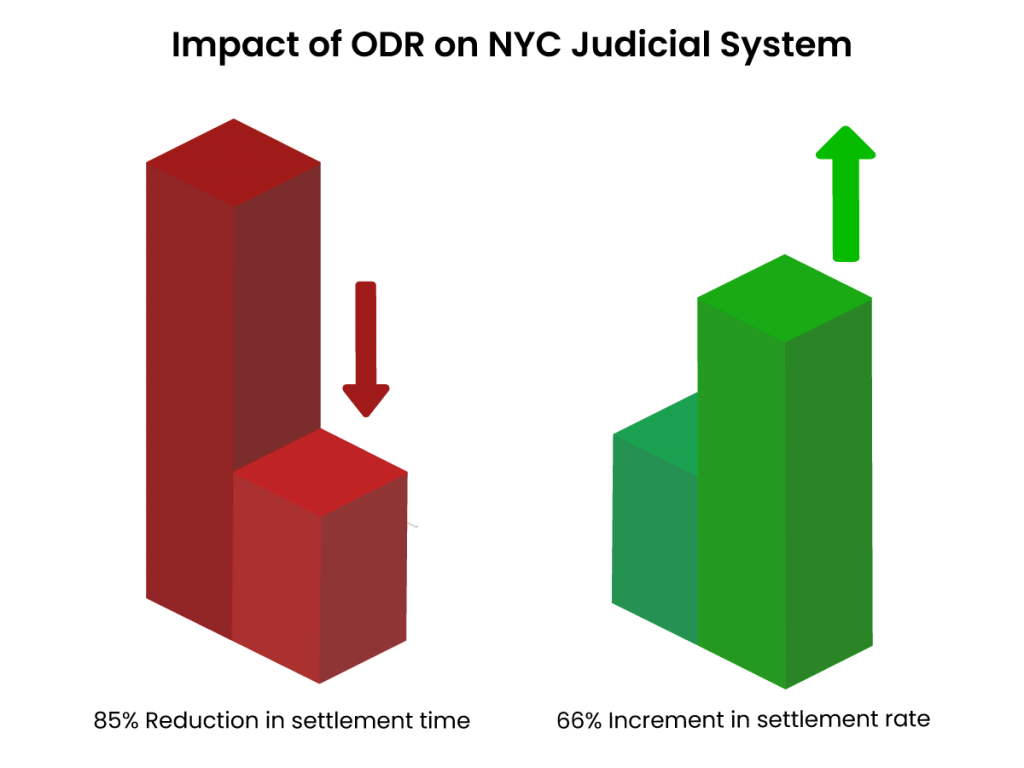

The success of private ODR platforms led to the government of various countries adopting the mechanism in their judicial system. The city of New York was one of the first to adopt an ODR system to clear its backlog and expedite the settlement of personal injury claims.

The adoption of ODR in New York was a success as it resulted in reducing settlement time by 85%, as well as an impressive 66% settlement rate within 30 days of the submission of the dispute.

Consumidor, the Brazilian ODR platform for consumer disputes, also seems to be thriving, having resolved over 2 million consumer disputes in the last five years[11].

Other notable examples of court-annexed ODR include the Civil Resolution Tribunal in British Columbia, Canada; Money Claim Online in the United Kingdom; and the New Mexico Courts Online Dispute Resolution Centre in the USA.

The following are a few detailed case studies of ODR being used globally:

1. Civil Resolution Tribunal: The British Columbia Civil Resolution Tribunal (“CRT”) is Canada’s first online tribunal which deals with the resolution of motor vehicle injury (up to CAD 50,000), small claims (up to CAD 5,000) and strata property (condominium) and societies and cooperative association disputes. The CRT has been a part of British Columbia’s public justice system since 2016 and has a unique 3-stage dispute resolution mechanism.

Once the application made by the claimant has been accepted, the disputing parties can negotiate via the secure and confidential platform. If the parties reach an impasse in the first stage, a case manager will be assigned who will assist in reaching an agreement.

These agreements can be turned into orders and can be enforced as a court order. If parties don’t reach an agreement in the first two phases, an independent CRT member will make a decision about the dispute. A CRT decision can be enforced like a court order. Out of 14,482 disputes registered until December 2019, CRT closed 12,912 out of them.

These closed disputes include withdrawn claims, disputes resolved by agreement, cases where the CRT refused to issue a Dispute Notice, disputes resolved by default or tribunal member decision, and other reasons for closure.

2. Electronic Business Related Arbitration and Mediation (“eBRAM”): eBRAM (cofounded and supported by the Hong Kong Bar Association, Law Society of Hong Kong, Asian Academy of International Law Ltd., and Logistics and Supply Chain MultiTech R&D Centre Ltd.) is building an Online Dispute Resolution platform to support business-to-business transactions in the APEC Region.

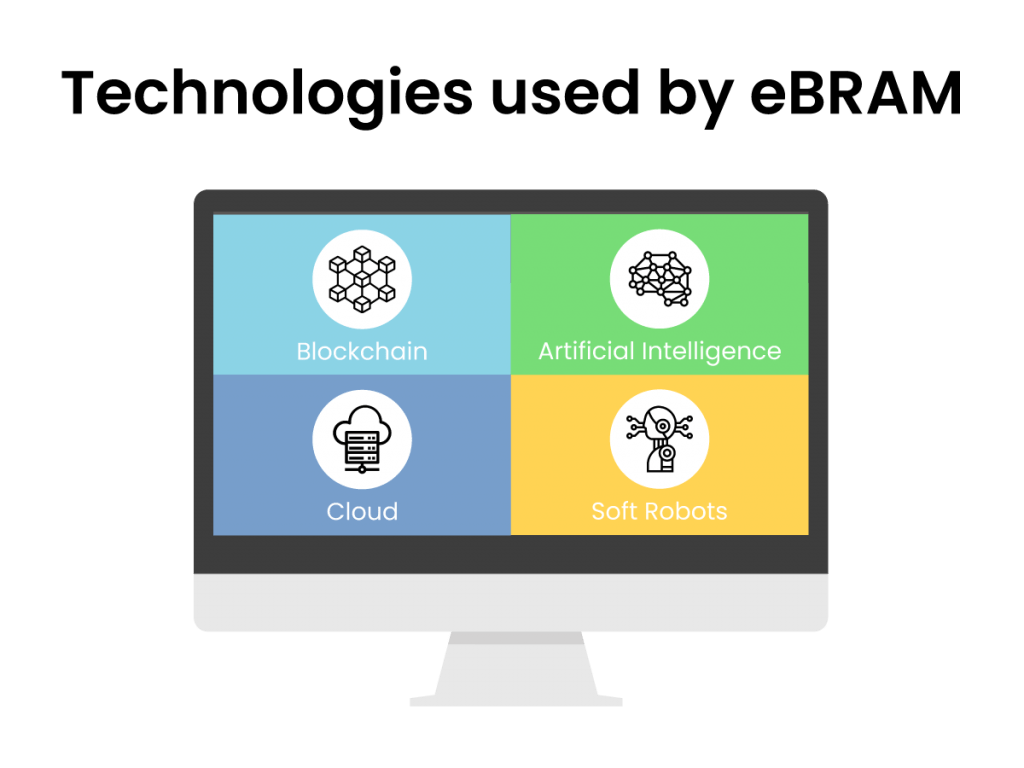

It aims at providing a user-friendly and secure platform to negotiate contracts and resolve disputes in a fair, cost-effective, speedy, and secure manner through mediation, negotiation, and arbitration. It is using emerging technologies, including blockchain, artificial intelligence, soft robotics, and cloud, in facilitating its services. The platform was launched in early 2022 and received an allotment of USD 19.1 million for its first six years.

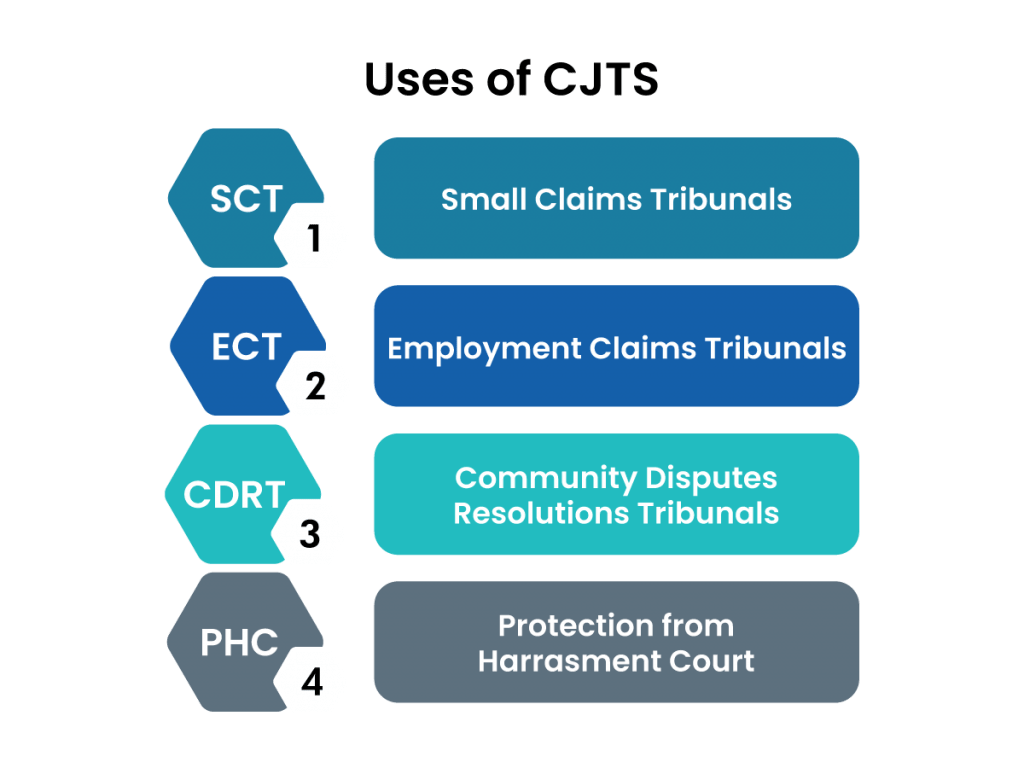

3. Community Justice and Tribunal Systems (“CJTS”): The State Courts in Singapore have introduced CJTS, an electronic case filing and management system, which allows parties involved in small claims disputes to file claims and access court e-services from the comfort of their homes and offices.

The system also has an e-negotiation feature, which allows the parties to negotiate and reach a settlement on the disputed claims without having to go to the courts.

Ananya Singhal and Dhriti Hundia are members of the Research and Content team at Presolv360.

[1] Source: State of the Indian Judiciary – A Report by Daksh, https://www.dakshindia.org/india-justice-report-2019/

[2] Source: India Legal

[3] Source: India Legal

[4] ODR Handbook, https://disputeresolution.online/

[5] E-Court India Services: https://ecourts.gov.in/ecourts_home/

[6] Source: https://www.prsindia.org/theprsblog/examining-pendency-cases-judiciary

[7] Source: https://www.latestlaws.com/articles/justice-delayed-is-justice-denied-issues-solutions-pertaining-to-pendency-in-indian-judiciary-by-kavisha-gupta/

[8] supra 1

[9] Source: State of the Indian Judiciary – A Report by Daksh

[10] Source: https://www.prsindia.org/theprsblog/examining-pendency-cases-judiciary

[11] Success or Failure? – Effectiveness of Consumer ODR Platforms in Brazil and in the EU, Copenhagen Business School Law Research Paper Series No. 19-17, file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/SSRN-id3374964.pdf